It’s been a long two weeks since lovely Copán, since reading in a hammock while the rain thunders on the tin roof, since eating a slice of flan de cafe – que rico!, since the significant decrease in my stress levels.

This will sound strange, but my favorite part of the Ruins is the macaws. Near Copán is a macaw rehabilitation center. Once the birds are healthy enough to start being reintegrated into the wild, they are brought to the Ruins and supplied with food, sheltered perches, and freedom to explore the park. The birds’ plumage is early Technicolor, like Wizard of Oz or Oklahoma! The reds and yellows and greens pop like freshly applied paint in an Andy Warhol painting. The birds swoop and soar between the trees. They screech loudly and repeatedly. At one point we are in the middle of a group chatting from the depths of the tall trees. Two birds on a branch are fighting or flirting. There are no cages, no signs, only trees, noise, and these birds. They are fantastic, vibrant, and this is definitely one of those Mr. Macaw, I’m not in Kansas anymore moments.

This will sound strange, but my favorite part of the Ruins is the macaws. Near Copán is a macaw rehabilitation center. Once the birds are healthy enough to start being reintegrated into the wild, they are brought to the Ruins and supplied with food, sheltered perches, and freedom to explore the park. The birds’ plumage is early Technicolor, like Wizard of Oz or Oklahoma! The reds and yellows and greens pop like freshly applied paint in an Andy Warhol painting. The birds swoop and soar between the trees. They screech loudly and repeatedly. At one point we are in the middle of a group chatting from the depths of the tall trees. Two birds on a branch are fighting or flirting. There are no cages, no signs, only trees, noise, and these birds. They are fantastic, vibrant, and this is definitely one of those Mr. Macaw, I’m not in Kansas anymore moments.

The ideal way of experiencing the Ruins must be with a guide, because while there are signs explaining the ages of the statuary and pyramids (600 A.D. onward), their context is a cipher. That’s not to say I am not awed by the structures, only that I don’t have enough context to fully appreciate them. I have to admit I have a difficult time in museums. I often need a story, not just the facts, to fully appreciate the artistry. I’m a little embarrassed of this failing as a semi-educated person. I will return to Copán in the spring and will definitely hire a guide to explain just what that tortoise means and the pyramids and the symbols on the altars.

Monday starts with chasing the Independence Day parade(s), because I love marching bands. The sound and feeling of thundering drums combined with thick brass—forget the winds—gives me chills and teary eyes. In 2000 (according to IMDb), a small movie called Our Song, about three Brooklyn girls in a high school marching band, came out. It opened with the band playing and I immediately teared up. Between the drums and bittersweet story of friendship, my eyes were not often dry. There’s a band called The Last Regiment of Syncopated Drummers in Portland that I fantasize about joining.

We stand in the town square crowded with food vendors, kids in school and band uniforms, occasional tourists, and a young woman with a golden fan headdress topped with dried grasses and long woven skirt of the same dried grasses, surrounded by people with cameraphones. It’s unclear if we’ve missed everything. Then the drums and glockenspiels start at the opposite end of the square. The sidewalks fill with onlookers. I stand on a wall, unable to see anything (the visual element seems important for the chills), but ten minutes in, drums start on another side of the square. I dash over and have a front row view of the drummers, glockenspiels, and kids with pom-pons and banners expressing peace, god, love, and history. My nose tingles and weeping beckons, but I hold it in. Once that section of the parade moves on, another band starts at a third side of the square. I never do figure out if the parade has any official beginning, because as soon as one section of it ends, another section starts elsewhere, this time a block in the opposite direction. The parade is modest, with the occasional vaquero or traditional dress outfit, but mostly school uniforms and banners. So many schools for such a small town, at least 15, and the bilingual school is so much larger than CBS…and the female volunteers teachers are mostly tall, strong, and blond—is this a requirement? There is a float of Noah’s Ark and a crowd of kids with Halloween masks. Many of the kids wear sunglasses, lending a secret agent or too cool for school feeling to the whole event. I lose my fellow volunteers early on. A whisper wonders if they might worry and try to call my phone, left behind in the room, but I just don’t care. This is for me.

We stand in the town square crowded with food vendors, kids in school and band uniforms, occasional tourists, and a young woman with a golden fan headdress topped with dried grasses and long woven skirt of the same dried grasses, surrounded by people with cameraphones. It’s unclear if we’ve missed everything. Then the drums and glockenspiels start at the opposite end of the square. The sidewalks fill with onlookers. I stand on a wall, unable to see anything (the visual element seems important for the chills), but ten minutes in, drums start on another side of the square. I dash over and have a front row view of the drummers, glockenspiels, and kids with pom-pons and banners expressing peace, god, love, and history. My nose tingles and weeping beckons, but I hold it in. Once that section of the parade moves on, another band starts at a third side of the square. I never do figure out if the parade has any official beginning, because as soon as one section of it ends, another section starts elsewhere, this time a block in the opposite direction. The parade is modest, with the occasional vaquero or traditional dress outfit, but mostly school uniforms and banners. So many schools for such a small town, at least 15, and the bilingual school is so much larger than CBS…and the female volunteers teachers are mostly tall, strong, and blond—is this a requirement? There is a float of Noah’s Ark and a crowd of kids with Halloween masks. Many of the kids wear sunglasses, lending a secret agent or too cool for school feeling to the whole event. I lose my fellow volunteers early on. A whisper wonders if they might worry and try to call my phone, left behind in the room, but I just don’t care. This is for me.

The final adventure of our trip takes us to the Luna Jaguar Hot Springs, a mostly beautiful and bumpy hour ride away on a rain-soaked mattress in the back of a truck, where Eza and I attract quite a bit of attention and whistles. I mentioned earlier not really fitting in with my co-volunteers. One-on-one, conversations about topics other than drinking or mocking classmates from high school can take place.

I’ve always wanted to go to a hot spring. There are several near Portland, but…it’s just never happened. For some reason the adventures close to home rarely are explored. I can’t imagine any spring would ever compare to this, however, and, again, my descriptive abilities are challenged. It is raining hard. We are lead over a swiftly moving river across an occasionally slippery rope and plank bridge into dense forest. We pass through a narrow tunnel and to the right is a cascade of small pools. The path winds around and there are yet more pools alongside a stream. The pools are cloudy and surrounded with flat rocks. After a brief tour and explanation of the pools’ temperatures, we strip down into bathing suits—I am the only one without a bikini—and venture back down the stony path to the first spring, and then the second, and third, and beneath a warm waterfall, only to climb higher until we’re level with the top of a steaming waterfall. The rain has cooled the air so sitting in warm-to-hot pools of water in a humid environment is thoroughly pleasant, romantic, and I’m ready to move in. And it is so quiet aside from the rushing water; Honduras is not a quiet country. Until the very end, we are the only visitors. After at least an hour we conclude at that cascade of small pools. Each is warmer than the next until we reach the final, largest, and hottest pool of them all, too hot for everyone but me. I relish hot baths, especially in the winter when my fingers and toes are often numb and swollen, and if I miss any luxury on my adventure down here, it’s reading in a hot bath with a book. I soak and float, and by this time my feet, all of our feet, are cleaner than they have been in a month. Actually, the final pool is a cold water pool, and I do dare to slide my full body in , and it feels as if fine bristled brushes are pressed against my skin and my body were poured lead. I laugh.

I’ve always wanted to go to a hot spring. There are several near Portland, but…it’s just never happened. For some reason the adventures close to home rarely are explored. I can’t imagine any spring would ever compare to this, however, and, again, my descriptive abilities are challenged. It is raining hard. We are lead over a swiftly moving river across an occasionally slippery rope and plank bridge into dense forest. We pass through a narrow tunnel and to the right is a cascade of small pools. The path winds around and there are yet more pools alongside a stream. The pools are cloudy and surrounded with flat rocks. After a brief tour and explanation of the pools’ temperatures, we strip down into bathing suits—I am the only one without a bikini—and venture back down the stony path to the first spring, and then the second, and third, and beneath a warm waterfall, only to climb higher until we’re level with the top of a steaming waterfall. The rain has cooled the air so sitting in warm-to-hot pools of water in a humid environment is thoroughly pleasant, romantic, and I’m ready to move in. And it is so quiet aside from the rushing water; Honduras is not a quiet country. Until the very end, we are the only visitors. After at least an hour we conclude at that cascade of small pools. Each is warmer than the next until we reach the final, largest, and hottest pool of them all, too hot for everyone but me. I relish hot baths, especially in the winter when my fingers and toes are often numb and swollen, and if I miss any luxury on my adventure down here, it’s reading in a hot bath with a book. I soak and float, and by this time my feet, all of our feet, are cleaner than they have been in a month. Actually, the final pool is a cold water pool, and I do dare to slide my full body in , and it feels as if fine bristled brushes are pressed against my skin and my body were poured lead. I laugh.

The other delights of Copán are small. I taste genuine pupusas, a type of cornflour pancake filled with cheese, beans, and/or meat, a foodstuff previously eaten only at home through the efforts of my unskilled hands; drink a decaffeinated (bad tummy) espresso; and spend several hours with a book (Cloudstreet by Tim Winton, and you should read it right now) in a rooftop hammock. I meet an Australian traveler who asks me questions, rather than the interest being on only my side (see co-volunteers). Also, speaking of whiteness, since the residents are used to tourists, there is much less gawking and catcalling. I see white tourists and Asian tourists. And we walk anywhere comfortably, without warnings of danger. The views from the hills of the city are spectacular.

For these days I’ve done my best to bury school in a dusty corner of my mind, yet it unearths, of course. We leave Tuesday morning, with minimal transportation drama. Then it is back to lesson planning and stressing over teaching the formation of the universe.

As I write this entry, the pleasures of Copán are difficult to comprehend, buried as I am in the dramas of school. I look forward to the next break, at the end of October.

Endeavoring,

theresa

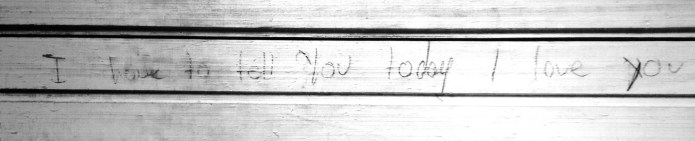

P.S. I love you, Erpie!